A Chronicle of Resistance, Advocacy, and Unapologetic Truth

Before hashtags trended, before retweets amplified outrage, and long before TikTok became a megaphone for dissent, I was already speaking. Not for clout. Not for applause. But because silence was never an option. My fight for democracy, human rights, leadership integrity, and the dignity of Kenya’s most marginalized and minority groups began in 2006, and it has never paused, never wavered, never needed a spotlight to matter.

Back in 2007, I wrote two opinion pieces, one in Daily Nation, the other in The Standard. The articles were bold and blunt, calling out the moral bankruptcy of our political class and the corrosion of ethics in public life. Corruption was the beast I pointed at then, and it remains the beast today. That was long before many Gen Zs could read a newspaper.

Even earlier, in 2006, I took on a subject most people ignored: the treatment of security guards. My article demanded respect and better pay for this silent workforce that guards banks, malls, and private homes, but is rarely guarded by decent wages or legal protection. It’s now nearly two decades since I made that call. The industry still suffers from the same injustices. Same script, same neglect.

That same year, as a print journalist, I also raised the alarm on road safety, long before boda bodas became Kenya’s daily death sentence. I wrote about the rise of boda boda bicycles in Kisumu, when owning one in the village was like owning a car. I warned that without serious regulation, these bikes would become weapons on wheels. And today, sadly, they have. The same riders who once peddled bicycles now ride motorcycles, having transferred their recklessness from pedals to engines with deadly consequences.

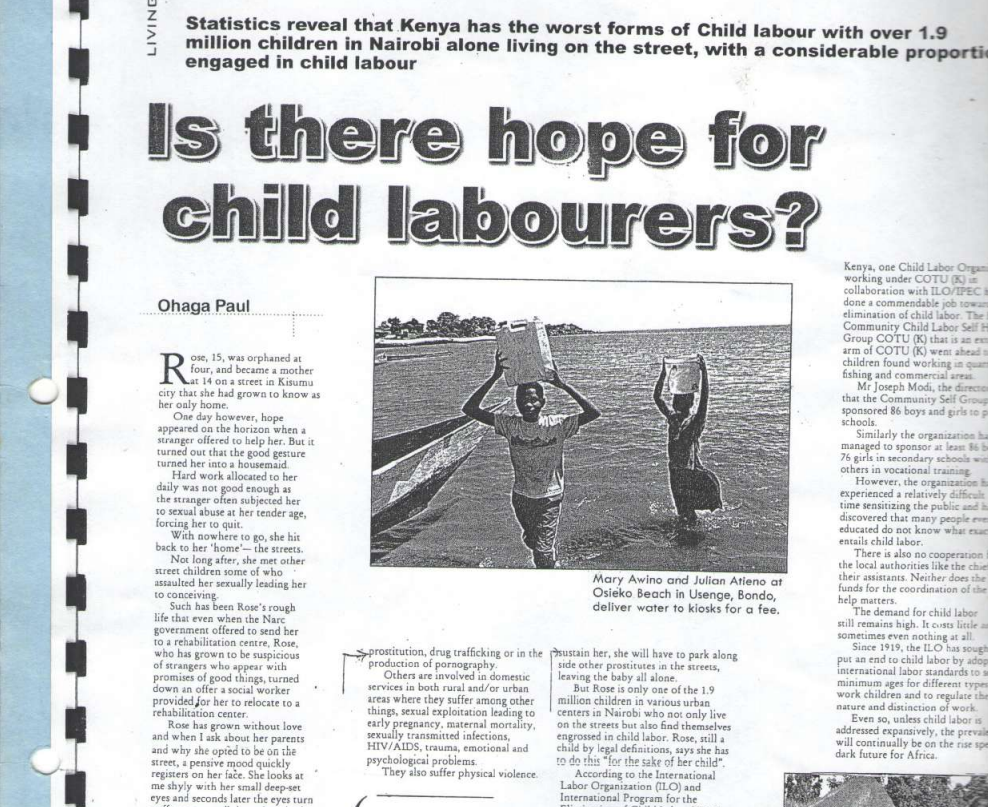

Still in 2006, I raised concerns through an article titled Is There Hope for Child Labourers? published by the then Kenya Times. In the piece, I argued for the urgent protection and safeguarding of children’s rights to prevent the widespread exploitation of child labour. I highlighted how child labour is often viewed as an inevitable part of life for the poor, perceived not as exploitation, but as a necessary survival and coping mechanism for families living in poverty.

In 2008 and 2009, I transitioned to radio. At a community station in Nairobi, I created and hosted a program called Focus on Kibera, inspired by the BBC’s Focus on Africa. The goal was urgent: to spotlight the complex web of challenges facing Kibera’s residents—from the lack of proper infrastructure to poor sanitation, insufficient water supply, insecure electricity, bad roads, poverty, insecurity, and rampant unemployment. I also produced features on persons living with disabilities (PWDs), aiming to sensitise the public and policymakers to the neglect and everyday struggles they face, advocating for visibility, policy, and dignity.

That work laid the foundation for my next chapter. In 2011, I transitioned into the NGO world, beginning in Bondo and Rarieda in Siaya County. I worked with sex workers, people living with HIV, men who have sex with men (MSM), and fisherfolk communities—groups often reduced to whispers in policy discussions. I travelled through Kisumu, Busia, Migori, Turkana, Pokot, Homa Bay, Nyatike, and Nairobi, pushing for access to healthcare and social justice.

Sitting with sex workers taught me that these were not “taboo tales”—they were stories of survival. No woman wakes up and chooses to sell her body unless the world gives her no other option. We offered biomedical and structural support, but what stayed with me was the dignity of their struggle—and the indifference of society. I documented this during COVID-19, when most looked away. I didn’t. Read: Sex Workers Face a Dilemma: To Work or Not During COVID-19 – African Arguments.

I also turned the spotlight on persons with disabilities during the pandemic and addressed the rise of domestic violence in lockdown homes. I wrote about the rights and dignity of the elderly—a group that often disappears from our national conversations.

On Media, Gender, and Freedom

Media freedom? I’ve been vocal, persistent, and unrelenting. I’ve challenged shrinking civic spaces and the slow censorship creeping into our airwaves and screens. I’ve called out the tendency to gag journalists and punish truth-tellers.

I warned that governments were using COVID-19 as a smokescreen to silence journalists and clamp down on dissent:

- World leaders must not use COVID-19 to suppress media freedom – Daily Nation

- Kenyans must protect media freedom now more than ever

- Media too need a helping hand to get through the pandemic

- Media freedom in Kenya under renewed threat – Citizen Kenya

- Deputy President Gachagua’s attacks on media not good for democracy

I’ve also written about the tension between privacy rights and online expression, and the dangerous rhetoric against social media. Read: The War on Social Media and Why CS Kagwe is Certain to Lose.

Equally, I’ve defended gender inclusivity in all its complexity. Not just women’s rights—but men’s rights too. In this piece on GBV, I pushed for a conversation that doesn’t flatten nuance or silence male victims.

On leadership, I’ve challenged institutions and icons. I called for Francis Atwoli’s exit—not from spite, but in favor of generational renewal. That piece stirred debate not just about Atwoli, but about our addiction to power retention across all spheres. Read it here.

The Cost of Speaking Up

I’m not neutral. I am truthful. And yes, my journalism, thoughts, and writing are activist in nature. That’s not a flaw—it’s a stand. I don’t write to impress. I write to disrupt, to question, to demand better.

During the Gen Z–led protests that began in 2024 and have continued ever since, I used my camera to document the movement, capturing images, recording moments, and risking my life over and over again. The June 2025 protests nearly cost me everything. I survived death three times: twice at the hands of the police, and once in the grip of hired goons.

Still, I Believe in Kenya

Still, despite broken systems, I believe in Kenya. But I’ve come to realise something uncomfortable: many Kenyans are like the Israelites who blamed Moses for taking them out of Egypt. They have adapted to captivity. So long as there’s a paycheck, a little food, foul tap water, blackouts they’ve normalised, and roads that break more bones than they fix, they carry on. When someone dies because of this rot, they don’t organise protests or demand reforms; they form WhatsApp groups to fund the funeral.

Salvation, even in faith, is for those who seek it. Even Jesus can’t save someone who refuses help.

To those still fighting for a better Kenya, don’t stop.

To those content in captivity, keep living.