In colonial America, long before modern constitutional protections existed, a German-American printer and journalist named John Peter Zenger was arrested and charged with criminal libel for publishing criticisms of the then-New York Governor, William Cosby. Through his newspaper, The New York Weekly Journal, Zenger accused the governor of corruption. At the time, the law on seditious libel was clear: criticizing authority was a punishable offense, regardless of whether it was true. But Zenger’s defense attorney, Andrew Hamilton, argued before the jury, “The question before the Court and you, gentlemen of the jury, is not of small nor private concern. It is not the cause of one poor printer, nor of New York alone. It is the cause of liberty.”

The jury sided with Zenger. That single case became a cornerstone for press freedom and the legal doctrine that truth is a defense to defamation. Fast-forward to today. In modern Kenya, the debate remains: when does free speech end and defamation begin?

Today, in Kenya, freedom of expression, press freedom, and access to information are constitutionally protected under Articles 33, 34, and 35 of the 2010 Constitution. Yet, that same Constitution, along with statutory and common law, criminalizes and civilly punishes defamation.

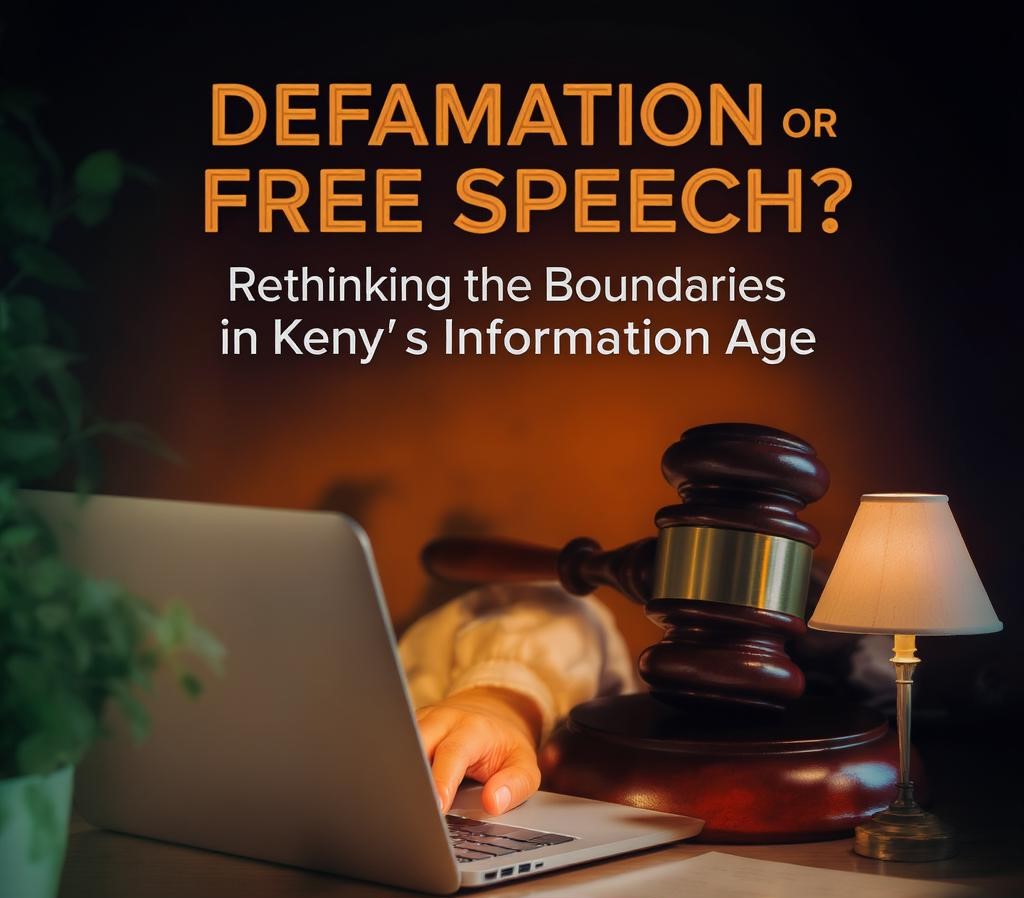

This raises a fundamental question: does the existence of defamation laws undermine the same freedoms the Constitution guarantees?

Let’s break it down.

If someone calls you “stupid,” have they defamed you or simply insulted you? What if they say your actions were stupid? Does that carry the same legal weight? Defamation, after all, is about injury to reputation through false statements presented as fact. But what about satire, opinion, hyperbole, or genuine critique?

Consider the high-profile defamation case involving Jimmy Wanjigi. During the tense 2017–2018 election period, the Daily Nation ran an obituary falsely announcing Wanjigi’s death. Whether through editorial negligence or ill intent, the paper later admitted the error. Wanjigi sued, and in July 2019, the court awarded him KES 8 million in damages. The court emphasized that the publication was not only false but caused harm to his reputation and psychological well-being.

So, why did the court rule in Wanjigi’s favor? Because even in a democratic society, freedom of speech is not absolute. As Article 33(2) of the Constitution clarifies, expression does not extend to hate speech, incitement to violence, or malicious falsehoods.

What the Nation case demonstrates is that even a respected media outlet can be held liable if due diligence fails. An obituary—an ad that passes through editors, proofreaders, and revenue officers—cannot be passed off as “public interest journalism” or protected opinion.

This incident isn’t isolated. Other defamation cases continue to shape Kenya’s legal landscape: Boss Shollei vs. The Standard Group, where false claims regarding alleged misconduct led to a damages award of over KES 20 million. Cyprian Nyakundi vs. Bob Collymore, where the late Safaricom CEO sued over defamatory blog posts. Robert Alai, repeatedly charged with defamation for tweets, and a blogger, Julius Muriithi (2014) sentenced for defaming Uhuru Kenyatta via Facebook under Section 29 of the Kenya Information and Communications Act (later repealed in 2016).

These cases reveal two truths:

- Media freedom must be protected, especially in matters of public interest.

- But freedom must be exercised responsibly, grounded in truth and public good, not sensationalism or malice.

As Kenya’s digital media expands, so do legal questions: Should satire be immune? Can public figures tolerate more criticism than private citizens? Is it defamation if it’s true but damaging? Should criminal defamation be abolished altogether?

Maybe the answer lies where it all began: in Zenger’s trial. Defamation laws should exist, but only to protect reputation without silencing truth. In the digital age, with anonymous blogs, viral posts, and political propaganda, courts must remain vigilant, but so must journalists. Freedom of expression is not a license to harm. But neither should fear of litigation muzzle truth.

Ohaga Ohaga is a Kenyan Journalist, Writer, and Communication Specialist with a special interest in Media Law and Political Communication. He remains a close observer of, and participant in, Journalism and the Media