In an age where machines now paint, write poetry, remix music, and even mimic human emotion, a simple yet urgent question confronts us: Who owns AI-generated art?

Across the world, this question has sparked heated legal, philosophical, and cultural debates. The U.S. Copyright Office, for instance, has refused to register works produced solely by artificial intelligence, insisting that copyright protection requires meaningful human authorship. Europe and the UK have taken similar positions, denying AI the legal status of “inventor” or “author.” These views echo Enlightenment-era notions that creativity is a uniquely human trait, tied to consciousness, moral intent, and emotional depth.

But AI isn’t waiting for permission. Tools like ChatGPT, Midjourney, and DALL·E are already shaping the future of art and storytelling. In Kenya, musicians, illustrators, and filmmakers are cautiously embracing these technologies—using them to brainstorm, polish scripts, or experiment with new visual styles. And yet, the law remains frozen in time.

Kenya’s Copyright Act (2001, revised 2019) does not recognise AI as a creative agent, nor does it provide a legal framework for hybrid authorship, where a human and machine collaborate to produce a work. Worse, it offers no guidance on ownership of AI-assisted creations. As it stands, a Kenyan artist who uses an AI tool to co-create a music track or digital painting has no clear legal claim to that work.

This is more than a technical gap. It is a legal vacuum that puts our artists, especially younger and digitally-savvy ones, at risk. Without reform, their creations may be vulnerable to appropriation, exploitation, or even erasure in global digital platforms where Western tech companies dominate the infrastructure and the profits.

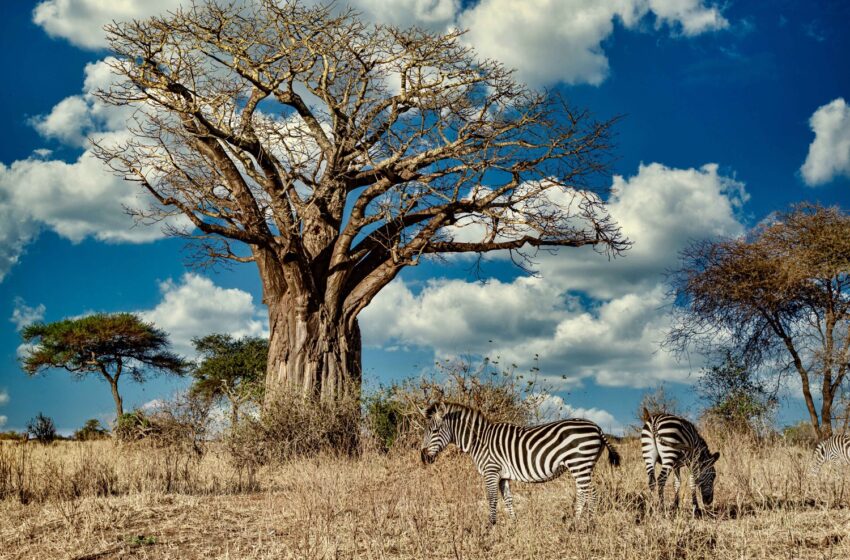

It gets more complicated. Much of today’s AI is trained on massive datasets scraped from the internet—including African stories, music, languages, and designs—often without consent, credit, or compensation. A 2023 MIT audit revealed that over 70% of online “Maasai” images used in AI datasets were captured and tagged by non-African sources. The result? Misrepresentation, distortion, and digital colonialism.

The Kenyan government, like many others in the Global South, is playing catch-up. While countries like Brazil have passed laws requiring informed consent from Indigenous communities before using their cultural expressions in AI training, Kenya has yet to even acknowledge the issue. Our lawmakers still treat intellectual property as an individualistic, Western-imported concept—ignoring the collective, oral, and symbolic nature of African creativity.

Globally, a growing number of scholars and artists are pushing back against this outdated model. They argue for ethical AI rooted in cultural sovereignty and inclusivity. They call for laws that protect not just economic rights, but moral rights—ensuring that art created with the help of AI honours its sources, respects communal heritage, and avoids reinforcing global imbalances.

Kenya must join this conversation.

First, Parliament should amend the Copyright Act to recognize hybrid authorship—ensuring that artists using AI have enforceable rights over their creations. Attribution, transparency, and informed consent must be enshrined in law, particularly where cultural data is involved.

Second, Kenya should develop ethical guidelines for AI training, requiring tech firms to disclose their data sources and include African communities in decisions about how their culture is used and represented. This is not just a legal matter; it is about dignity and self-determination in the digital age.

Third, we need investment in local AI tools built by and for African creators. Initiatives like Nigeria’s YorubaGPT or Kenya’s Samburu Beadwork AI Project show what’s possible when cultural heritage meets innovation. These efforts not only preserve tradition but also create new forms of artistic expression that speak to global audiences on our own terms.

Finally, legal literacy must be a national priority. Most Kenyan artists remain unaware of how copyright, fair use, or AI ethics affect them. Without education and outreach, any reforms risk becoming mere paper protections.

The future of art is being coded right now—line by line, dataset by dataset. If Kenya wants to protect its creative economy, honour its cultural heritage, and empower its artists, it must not sit on the sidelines. It must act boldly, urgently, and ethically.

Otherwise, we risk becoming spectators in our own story.

Ohaga Ohaga is a Kenyan journalist, writer, and communication specialist with a special interest in media law, digital culture, and the intersection of technology and identity.